How Latinos Changed My Life

“A story about overcoming our own biases…is exactly the kind of story we need to hear in America. We should (discuss) in a truthful and mature and responsible way the divides that still exist — the discrimination that’s still out there, the prejudices that still hold us back — not on cable TV, not just through a bunch of academic symposia or fancy commissions or panels, not through political posturing, but around kitchen tables, and water coolers, and church basements, and in our schools, and with our kids all across the country.”

— President Obama, National Urban League, July 29, 2010

(NOTE: I go into the complexities surrounding immigration, including both poverty and overwhelmed public services especially in border states, in a national feature story called A People on the Move. In this article I show that, until we find a legal solution, it pays to get to know our Latino neighbors.)

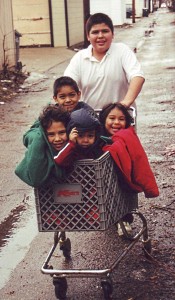

I confess, when my family moved to a South Minneapolis neighborhood in July of 2000, I reacted out of ignorance. What? Did I just see a grocery cart full of Latino kids disappear down our alley, motored by a stocky, impish-looking teenager? To a photojournalist this was tantalizing, so I bolted up the stairs to grab my camera.

As a white, middle-class parent, my first feelings were “Oh, great. So here are our children’s new neighbors–poor, out-of-control latchkey kids, unashamed to play with stolen property. Don’t they know any better? Is this teenager holding them hostage?”

But one year later, we knew not only this Latino teen’s name and face – we knew his story. Manny’s mother was “somewhere” in prison, and his father was probably deported. He lived with his grandmother, did his best to contain his resentment, and mowed our lawn to pay for his school notebooks.

But one year later, we knew not only this Latino teen’s name and face – we knew his story. Manny’s mother was “somewhere” in prison, and his father was probably deported. He lived with his grandmother, did his best to contain his resentment, and mowed our lawn to pay for his school notebooks.

In the years ahead, my relationship with Manny and dozens of other Latino neighbors became transformative. This does not change my sympathy for border state attempts, however imperfect, to manage their civic affairs. In fact, out-of-state opponents of Arizona’s attempted “Passports Please” law only earn the right to criticize it by offering a better solution to multi-faceted problems that have overwhelmed the state’s civic services during a serious budget deficit.

Yet numerous face-to-face encounters have furnished a mirror with which to check my previously unchallenged, knee-jerk assumptions about a population that, if I were honest, was “alien” to me.

It gradually dawned on me, for example, that Manny didn’t have the club membership or sports equipment that my kids have. He was entertaining his younger cousins in the grocery cart in the best way he knew how.

The cart was not just “stolen” property but a poor family’s means of transporting heavy groceries, a “vehicle” that doubled as a toy. Suddenly I understood why a Red Flyer wagon was chained to a pole by the bus stop in our neighborhood right next to the weekly food distribution point of a rescue mission. It is a major daily challenge that evades car-owning middle-class Americans.

All of this brought to mind Mother Theresa’s words: “Today it is very fashionable to talk about the poor. Unfortunately, it is not fashionable to talk with them.”

EYE-OPENING MOMENTS AND LESSONS LEARNED

Those who are content to objectify Latinos as a “legal problem,” or treat them through cost-benefit analyses as “economic widgets,” or distort them as primarily members of gangs or drug cartels, probably will not hear President Obama’s national plea to U. S. citizens to use this race-sensitive season as an occasion to “turn inward,” share our stories, and “examine what’s in our own hearts.”

But for those who are game, the following confessions and lessons learned provide a chance to learn about the inevitable neighbors on our horizon, while we wait for the federal government to create more healthy terms for this immigrant relationship.

Marriage. At one o’clock in the morning, my wife and I were up listening to shouts and mariachi music bellowing from a house to the north of us, rising over the fence to the window of my 3-year-old, who was trying to sleep. My anger rose as I first called the police, then got dressed to make a more fair assessment of what was going on.

I proceeded through our gate, preparing my speech as I walked down the alley and turned the corner. But what I saw up close disarmed me. Wall to wall, festively dressed relatives were gathered, and before I could say anything, every guest turned, smiled, and beckoned me in, one bringing a drink with automatic, neighborly hospitality.

I came to find that relatives of a young couple were visiting from Chicago for a one-night celebration of their successful first year of marriage. Struck by the contrast to my own family’s relative isolation, I wondered at how American marriages could benefit from this kind of high regard and familial support. Could we who divorce more than 50% of the time have anything to learn from those whose marriages dissolve at less than a 15% rate?

I gave my neighbors the easy gift I could provide this young couple: improved cross-cultural understanding and a different solution for my daughter’s sleeping woes.

Hospitality. On a second occasion, we were invited by Latino neighbors across the street, total strangers, to a baby shower. We arrived late, again surrounded by smiling hospitality. We offered our congratulations with apologies because, like good Americans, we had schedules to keep and were too busy to stay. Undeterred, the mother loaded our arms with pastries, an ethnic dish, and soup, putting us to shame over our hasty exit and token gift of cookies.

Giving. Years later, my youngest daughter was friends with Angel, an aptly named buoyant neighbor just south of us, a handsome, pudgy school mate who boosted Hannah’s self-esteem as she beat him in running races every morning while waiting for the bus.

Our family will never forget when we threw a high school graduation party for our eldest daughter and the door bell rang. It was Angel, his hair slicked back, wearing a buttoned up white shirt, holding a beanie baby bunny. “I’m sorry, Rachel. This is all I have,” he said shyly, handing her his gift with a smile. Rachel’s gifts of money have all been spent, but Angel’s bunny remains a treasure on her shelf.

Hospitality, tight-knit family, and neighborliness were well-established practices in earlier American society that have, for many, all but faded from memory. Could Latinos be among our best mentors for remedial work in returning to values we long held dear?

Laughter. Need an emotional lift? Walk by an urban park in Minneapolis on a summer weekend, listen to the hoots and hollers of Latino men, and watch that speedy soccer footwork! Brothers, sisters, cousins and friends play their hearts out in south Minneapolis parks, having the times of their lives, invariably with joy-filled laughter.

This stands in contrast to the often serious and intense demeanor of the teenage basketball players I’ve coached who seem to get re-infected weekly with the “winning-is-everything” disease so typical of American sports. My contact with Latinos has helped me reclaim a childlike playfulness.

Business relationships. In our increasingly utilitarian world where business “networking” and “knowing somebody” is often unquestioned means to an end, I’ve learned from Latino business persons whose values may be instructive for our high-pressured “time-is-money” culture.

After telling me that 80 percent of the astounding 255 Latino businesses in our south Minneapolis Lake Street neighborhood are barely making it, consultant Monica Romero said, “That’s not negative or positive, because they want to be there for other reasons. Business is not just a source of income. It’s how they define their identity, relationship, and belonging in the community. It’s how they share their lives.”

This is best illustrated by a story told me by a Brazilian friend. Maria made her living by delivering fruit by bicycle each day to customers along a circular route. An American visitor suggested that it would be more efficient and profitable if she built a centrally located fruit stand so that customers came to her. Her response: “But then I wouldn’t get to visit the kids, families and friends along the way.”

With all the books today about the lost soul of business, perhaps it is time to borrow a leaf from Maria’s manual: the “customer is first” is not just a consumer appeasement strategy. It can be a way of life for those who have learned that we “work to live, not live to work.”

A SACRED RHYTHM TO LIFE

In celebration, business and daily life, our Latino neighbors have modeled to me a capacity to more peacefully and joyfully seize the opportunity occasioned by each new moment or person in my day. Trans-cultural time-perception surveys show what a contrast this is for the average American who is more likely to treat oneself to such enjoyment during “down times.”

It’s no surprise that surveys show Americans to be time-conscious and “task-oriented,” describing time as a “galloping horseman,” while Latinos, along with large segments of African and American Indian populations, are event-oriented, describing time as a “deep, still ocean.” For us, the goal is to accomplish “deliverables” on time. For them the concern is with “who’s there, what’s going on, and how one can embellish” a particular event.

I’m coming to understand why my teenage children often sincerely advise me to just “chill out.” But it helps when those around you are from cultures that see enough significance in seasons and rites of passage to even stop and celebrate an infant’s first fingernail clipping or haircutting. There is something both sacred and human when the community takes time to gather and a piñata is again dangled from the roof of my neighbor’s home.

I’m coming to understand why my teenage children often sincerely advise me to just “chill out.” But it helps when those around you are from cultures that see enough significance in seasons and rites of passage to even stop and celebrate an infant’s first fingernail clipping or haircutting. There is something both sacred and human when the community takes time to gather and a piñata is again dangled from the roof of my neighbor’s home.

Spontaneous compassion. In 2005 a few handymen from our church started a bimonthly home cleaning and repair outreach called Hands and Feet in our neighborhood. As our neighbors began to be increasingly Latino and we needed help translating, we invited a Latino pastor to lunch to discuss a partnership. Knowing he was passionate about serving his people, we were shocked when he refused.

We explained how well organized this Saturday event was. “This would only be once every two months.”

Surprisingly, his issue was not that he had too little time but that he would have too much time. He asked, “What about the other 59 days? Just call us any time and we will be there.”

This answer caught us right between the eyes. Having so organized our social programs to fit our schedules and satisfy our service quotas, what needs of our neighbors do we pass by every day?

Manny’s gift. As that grocery cart racer Manny ate at our table and played with our kids, we ultimately became one link in his safety net of relationships. But to us, Manny became much more.

One day Manny showed up on our porch, looking both proud and sad. Youth workers in our community had invited young Manny to be in the wedding party for their wedding, which was to begin in one hour, and Manny had nothing to wear. “Do you have a suit I could wear?” he asked sheepishly.

Picture this short, hefty teenager next to my tall, bean-pole frame. I had him by 10 inches. He had me by 50 pounds. I said, “Manny, you know I’d like to help, but I don’t see how you could fit into any of my clothes.”

Something about this challenge seemed uncomfortably reminiscent of gospel stories, so despite my misgivings, knowing there was no time to shop, I walked with him to my closet. We found a short-sleeved shirt that he could barely button, but on Manny my loosest slacks were ruffled and dragging. Just then, a contractor, who was working on our house, appeared with duct tape, “hemming” the extra slack up inside.

Manny pointed to my best tie–that part was easy–but then to my best suit coat. My first thought was, “Absent-minded teenager. He’ll take it off and leave it. I’ll never see it again.” But he insisted. “Please!” And now Jesus’ words, “If someone asks for your coat,” were ringing in my ears.

In fact, as I reflected, I became increasingly convicted. Maybe this is why Obama wants us to share our uncomfortable stories. Here were inspired urban youth workers giving a wedding party spot and a life memory to a kid to whom I could hardly lend a jacket.

What’s more, the open-invitation wedding was across the street from our home and we were, again, too “busy” to attend – but we’re learning. We’re stopping more often to appreciate life before it passes us by. Manny and his fellow Latinos have slowed us down, brought joy and spontaneity to our routine-driven, overscheduled lives, and openly shared their needs in a culture suffocating from self-sufficiency.

As smiling Manny walked off to church, reveling in the moment, hands disappearing within the sleeves of that gold-buttoned blazer, I wondered who was really more “alien” to the blessings life has to offer.

© 2012 Todd Svanoe. Unauthorized reproduction of this copyrighted material is prohibited.

—

Todd can be reached via the Contact page.

—

One Comment »

Leave a comment!

Great Article!